Before we begin – in order to get the most out of this article – try and keep an open mind. Make some effort to bear with me as the concepts we are about to unravel require earnest contemplation. However, if you find every word that follows to be utterly nonsensical, then please, by all means, try something else.

Still here?

Then, let’s go.

Ultimately, the concept of ‘being’ relates to 2 questions:

Who am I?

And what, is this?

Any potential theories we may encounter in the search for true meaning will assuredly fail to emulate the simplicity of the above questions that led us there.

Nonetheless, here’s an idea:

We may be living in a program. A simulated reality. Everything there is was, or will ever be – an illusion.

One question before you slam this browser tab shut:

How would you know?

But it’s Real…?

Our intuition cries out, of course. It all feels too real to be a simulation. The weight of the toast in the hand, the rich aroma of butter slathered upon it – it’s all white noise trickling along the periphery of our sentience. How could such sumptuous sophistication possibly be faked?

People often use Darwinian evolution as an argument that our views must accurately reflect reality. To them it’s obvious that our perceptions must be lucid when comes to reality for, otherwise, we would have been made extinct centuries ago.

Advocates of this idea are therefore insinuating that those who once saw existence for what it was boasted a serious competitive advantage over those who saw less accurately. Thus, Natural Selection made it more likely for them to pass on genes that enabled increasingly accurate perceptions.

As a result, we can be quite confident that we’re the offspring of those who saw accurately, and so we see accurately.

Iron-clad biology, right?

But Donald D. Hoffman, professor of Cognitive Science at the University of California, Irvine has disproved this argument with a single, irrefutable theorem:

According to evolution by natural selection, an organism that sees reality as it is will never be more fit than an organism of equal complexity that sees none of reality but is just tuned to fitness. Never.

-Donald D. Hoffman

In other words, someone who is fine-tuned to see only the ‘relevant’ parts of the universe can never be at a disadvantage to someone who can see the whole universe. therefore evolution – instead of opening our eyes, may actually be closing them in accordance with what is actually there versus we actually need to see in order to survive and thrive.

Now the doctrine of false reality has been somewhat embedded in the back of your mind, we can now delve into the origins of this speculation.

As it turns out, Simulation Theory is older than the bible.

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave:

Imagine you are one of many prisoners in a cave. You’ve all been in the cave since birth and are chained so that your legs and neck are immobile. Everyone is forced to look at a blank wall in front of them. Behind you is a fire. objects would move in front of the fire, casting shadows on the wall. These shadows are all you’ve ever known.

You cannot look at anything behind or to the side of you – you must look at the wall in front of you. As you’ve never had a chance to spot the ‘real’ objects before, you would take the projections of the thing to be the thing themselves. There would be no way to contradict ourselves.

The shadows become the objects. the simulation becomes the reality.

Our rate of progress

In 1982, ‘Pong’ was released to the world. It was a tennis-style game developed by Atari inc. in which players could compete. It featured simple two-dimensional graphics.

Now, scarcely 4 decades later, the progress in computer and information technology has been unprecedented. To say that video games have evolved is like saying describing light speed is ‘fast’ or the universe as ‘big’. The 1980s saw the arrival of 2D graphics, with 3D graphics emerging a few years later.

Now the 21st century has been ground zero of another technological explosion:

Virtual Reality.

The accelerated rate of progress when it comes to VR is by no means an over-exaggeration. Computers are able to power virtual reality simulators with extraordinary persuasive capacity. Computing power is directly correlated to the gaming experience.

Alongside this, the more we learn about how senses operate and how our brain functions, the more we will be able to create. This sustains the virtuous cycle between improvements in software (our minds and how they work) and hardware (the raw computational power required to go ever deeper into the unknown).

Even if the rate of progress diminishes by a factor of 1000 relative to its current trajectory, the extrapolated data still reveals that VR will, in due course, become indistinguishable from reality. When this occurs exactly is anybody’s guess, though it may be closer than you think.

Even the developers of such cutting-edge gadgetry will – at some point- find it immensely challenging to distinguish fiction from non-fiction. Knowledge and technology get better and better until, eventually, we could simulate just about anything.

But here’s my question:

How long before we could simulate everything.

No, hang on, better question:

What are the odds that we already have?

We could all be living in one great, big virtual state right now. but please, don’t take my word for it…

“Given that we’re clearly on a trajectory to have games that are indistinguishable from reality and those games could be played on any set top box or any PC, and their would probably be billions of computer or set top boxes, it would seem to follow that the odds we are in base reality are one in billions.”

-Elon Musk

One in billions. I’ll leave you to ponder that a moment.

Ancestor Simulations: Why Us?

Nick Bostrom – a Swedish philosopher from the University of Oxford – has a lot to say on this. He’s currently deemed a leading mind in the field of the anthropic principle and has boiled down the proposed scenario into 3 possible outcomes. In his words:

-

Intelligent civilisations never get to the stage where they can make such simulations, perhaps because they wipe themselves out first.

-

Intelligent civilisations arrive at that point but then choose for some reason not to conduct such simulations.

-

We are overwhelmingly likely to be in such a simulation.

He has postulated that an advanced civilization may opt to run “ancestor simulations” with the salient objective of ‘simulating’ their Homo Sapien forefathers. He explained it like this:

” It’s possible the vast majority of minds like ours do not belong to the original race but rather to people simulated by the advanced descendants of an original race. It is then possible to argue that, if this were the case, we would be rational to think that we are likely among the simulated minds rather than among the original biological ones.”

We are among the simulated rather than the original.

Ring a bell?

He also said this:

“That type of posthuman simulator would need sufficient computing power to keep track of “the detailed believe-states in all human brains at all times.” It would essentially need to sense observations (of birds, cars, etc) before they happened and provide simulated detail of whatever was about to be observed.

In the event of a simulation breakdown, the director — whether teenager or giant-headed alien — could simply “edit the states of any brains that have become aware of an anomaly before it spoils the simulation. Alternatively, the director could skip back a few seconds and rerun the simulation in a way that avoids the problem.”

Fixing the glitches as they occurred. Neat.

The number of simulated realities could run, ad infinitum. This abstraction becomes slightly easier to swallow once you understand that the artificial neural nets we are working on today are already being trained for recursive self-improvement/duplication in a simulated environment.

It is also speculated that – besides humans – these simulations may be the handiwork of advanced ‘Superintelligent’ AI or even an extraterrestrial race from the other side of the cosmos.

However, we must appreciate that this can seem a rather circular argument. If some super-intelligence were running simulations of their own “real” world, they could be expected to base its physical principles on those in their own universe, just as we do. In that case, the reason our world is mathematical would not be because it runs on a computer, but because the “real” world is also that way.

Bostrom’s three possibilities are also of an anthropocentric nature. It is an attempt to say something profound about the Universe by extrapolating from what humans in the 21st Century are up to. Predictions are all about comparing and contrasting events in the present.

In trying to conceive of what super-intelligent beings might do, or even what they would consist of, it’s only fitting that we start from ourselves. But that should not obscure the fact that we are then spinning webs from a thread of ignorance. The conclusion we arrive at is such that it boils down to: “We like science fairs and realistic games, I bet super-beings love them too!”

Alas, the truth is entirely unknown, but the entire premise of where we came from remains an interesting and impactful shower thought.

People fail to notice the direct link between evolution and upgrade. The idea of constant betterment. Constant improvement. We are all what you’d call trial and error. Existence is a trial because we are defined by a perpetual attempt to get better. Every day our task is to be the better teacher, friend, sibling, lover. But we have also made an error in setting our sights on perfection. We can never reach perfection. But we will never stop trying. And so the iteration continues…

One of the main arguments against then Simulation Hypothesis is that the computational power required to simulate everything – like to the subatomic level – would be practically impossible. Quantum computing would need to have a baby with the space-time continuum.

But who said you need to recreate absolutely everything? The minimal requirement lies within the confines of our virtual consciousness.

To put it simply, not every tiny detail need be created at once. Just enough to make us believe…

Schrodinger’s Cat

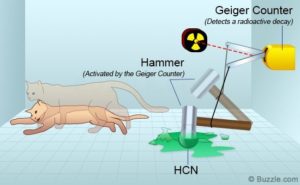

Erwin Schrödinger (1887-1961) was an Austrian-Irish physicist who came up with this infamous thought experiment, Schrödinger’s cat.

The idea is that a cat would be placed a box with some radioactive material and left to its own devices for a few hours. After the allocated time transpires, one must open the box to determine the fate of the feline. For the sake of the thought experiment, there was a 50 per cent chance the cat is dead and a 50 per cent chance the cat is alive.

Now, common sense would have us believe that the cat is already either alive or dead. Hence, we open the box to discover the truth.

But quantum physics tries to tell us that the cat is both alive and dead at the same time – that is until somebody opens up the box to verify. This is a counterintuitive belief that many will inevitably struggle to get their head around. But there’s just no way of knowing for sure until we see for ourselves. In essence, the contradicting truths do not annihilate one another since there exists no logical proof to suggest otherwise.

It is an analogical way of looking at superposition – the action of placing one thing on or above another, especially so that they coincide. A further example of ‘two things at once’ idea includes the notorious particle-wave duality of all matter and its implications in the field of quantum phenomena.

But this particular thought experiment gives us a far more exhaustive insight into the actuality of our circumstances. When it comes to any simulation – computer or otherwise – the thought experiment does hint at a cardinal rule when it comes to perception. It can be described as the Universe’s way of ‘hacking real life’.

Render only that which needs to be observed.

Stuff only really exists for as far as the eye can see.

Fake it till you Make it

“Reality is what we take to be true. What we take to be true is what we believe. What we believe is based upon our perceptions. What we perceive depends on what we look for. What we look for depends on what we think. What we think depends on what we perceive. What we perceive determines what we believe. What we believe determines what we take to be true. What we take to be true is our reality.”

-David Bohm, Theoretical Physicist

Back to gaming:

The onset of video game development could only really gain traction through the optimization of limited resources. If you asked somebody in the 1980s if you could render a game like Pistol Whip, a game offering a fully three-dimensional, virtual reality experience, they would say, “No.” if asked to elaborate, they’d protest that attempting such a feat would take all the computing power in the world and more. The brute force computations required would be not possible to implement in real-time.

So how come we’re playing that now?

Possibly the single biggest contributor toward our progression in this area is we’ve since worked out the golden rule of virtual environment design that we considered before – “only render that which is being observed.” Render too much and the computing power would be vastly depleted. But render too little, and it all feels terribly fake. It remains out of the question for one to lose themselves in a game in which they can see the environment being simulated before them. it needs to happen faster than our conscious minds are able to comprehend. Enter, optimization techniques.

Doom, a first-person shooter that became very popular in the 1990s, was the first to successfully administer such techniques. The optimization technique involved render only the light rays and objects that were clearly visible from the POV of the virtual camera. If it was outwith your field of view, it didn’t exist. Until you made it so.

Of course, optimization must also be taken out of the virtual context and applied to real-world complications.

Quantum mechanics, the branch of science dealing with subatomic particles, is one way we can examine the optimization technique at work. There are limits to the resolution with which one can observe the Universe, and if we try to study anything smaller, things just look “fuzzy”. It is akin to the pixelation of a screen when you stand too close.

Of course, as technology improves, so does our ability to look further and further. But, just as Doom manipulated the light rays to save computing power, and just as the cat is only dead when we see it as such.

All in all, it would still be enough detail to fool us. A lie is a fabrication. A good lie is believable. The best lie becomes subjective truth.

Perhaps we’re just living our best lie.

The Butterfly Dream

The following paragraph has been taken from the Philosophy Foundation:

Chuang Tzu was a philosopher in ancient China, who, one night went to sleep and dreamed that he was a butterfly. He dreamt that he was flying around from flower to flower and while he was dreaming he felt free, blown about by the breeze hither and thither. He was quite sure that he was a butterfly. But when he awoke he realised that he had just been dreaming and that he was really Chuang Tzu dreaming he was a butterfly. But then Chuang Tzu asked himself the following question:

“Was I Chuang Tzu dreaming I was a butterfly or am I now really a butterfly dreaming that I am Chuang Tzu?”

A character in a game is not aware they are in a game. Or even a character. Following from Plato’s allegory of the Cave, if the reality that they’ve acclimatised to is the only reality they’ve ever known, there resides absolutely no reason to question the legitimacy of the world around them as there is literally nothing else to compare with. But in a manner of ‘thinking outside the box’ as it were, even if one were to entertain the possibility that all is not what it seems, something still doesn’t sit quite right:

If this isn’t real then why am I seeing it?

To answer that we must return to the works of Hoffman and his ‘Evolutionary Game Theory’.

The Desktop Interface

Picture a blue rectangular icon on the lower right corner of your computer’s desktop. Does that mean that the file the icon represents is blue and rectangular and lives in the lower right corner of your computer itself? Of course not. That would be silly. But colour, position and shape are the only categories available with which to assert anything, and yet nothing is true of the file itself or anything in the computer. The map is not the territory. You could not truly describe the inner workings of the computer if your entire vantage point was constrained to the desktop.

The map is not the territory.

Nevertheless, shortcuts can be useful. That coloured rectangular icon guides behaviour, veiling a complex reality – a reality you don’t necessarily need to know.

This metaphor is extended to represent evolution. Evolution has shaped us with perceptions that allow us to survive. Such discernments have nudged adaptive behaviours in the optimal direction. But part of having the most seamless of user experiences involves hiding the stuff that proves inconsequential to us.

If reality could be fit into the ins and outs of a computer, our experiences would still be confined to the desktop interface. In this sense, 99% of reality, whatever reality might be, would be invisible. Granted, if you mistook a lion for a lampshade, it would be a problem. But equally, if you’d elected to spend all that time figuring out what the little blue icon really meant – the reality it represented – the lion would eat you anyway.

It’s not real

Experimental research in the field of cognitive neuroscience has confirmed that our brains default to ‘filling in the gaps’ when some aspect(s) of our observations don’t quite match up with what we expect. It thus becomes highly probable we have all hallucinated reality at some point. Furthermore, as this action takes place in the subconscious depths of our nature, we remain oblivious to the fact that everything is being rendered in real-time to align with the way we have been pre-conditioned to have and hold the world.

However, conventional wisdom reassures you that things are real because you are not the only one to vouch for the fact.

‘Other people see it too’.

Of course, we could all just be hallucinating together. Generating false ideas of our surroundings in perfect sync. But you’ll likely think that’s ludicrous, which is fine. Yes, it’s all very well and good seeing the same thing 7 billion of your peers are seeing.

Safety in numbers, as they say.

Until something happens to test that shared capacity. To cast a dividing line. To make us question the essence of what we actually know.

Something like this.

The Perfect Program

You and I live and breathe our collective mental model of the world. And we shall continue to do so, despite the fact it took two words to sever that model in half.

Finally, we must once again look to the future.

As we start building more advanced forms of Artificial Intelligence, do we choose to augment them in our image? To look, sound, think, feel, be like us. How would they perceive their world? Would they smile and frown? Love and hate? Laugh and cry? Live and die? But the most important question of them all… Would they believe it? Would all of this become their reality?

Of course, it would. Have you not been paying attention?

They’d be simulating mankind. Simulating… us. If we believe it, so will they.

The perfect computer program.

So I’ll ask you again:

Who are we?

What, is this?

But on that note:

Does it even matter?

Further Information:

We might live in a computer program, but it may not matter – BBC Earth (article)

The Turing Test – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (article)